CFPB Report Examines Risks of Home Equity Contracts

January 21, 2025

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) on Jan. 15 issued a report analyzing the risks associated with home equity contracts.

These contracts—often called home equity “investments” (HEIs)—are relatively new financial products in which homeowners get an upfront payment from a company and, in exchange, must repay a single lump sum repayment in the future that is based, in part, on the home’s value. The homeowner retains the right to occupy the home and assumes all ongoing financial obligations for the home. They must repay by the end of the contract term, often 10 to 30 years, or when a triggering event such as a home sale occurs. The repayment amount can be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars and is based on a formula that considers the home’s value and generally ensures that the repayment amount is significantly larger than the upfront payment under most home price scenarios, according to the CFPB.

Key findings:

Key findings:

- Consumers primarily use home equity contracts for debt consolidation and home improvements, though some consumers have reported that they use the funds for real estate investing or savings for or during retirement. The median home equity contract customer was in their 50s when they signed the contract and roughly 90% or more had mortgages that took a senior lien position to the home equity contract, according to a review of recent home equity contract securitizations.

- Home equity contracts are often marketed as an alternative to a cash-out refinance, home equity line of credit (HELOC), or traditional reverse mortgage loan, like a federally insured home equity conversion mortgage (HECM). Advertisements for home equity contracts tout large upfront payments and claim home equity contracts are not debt. Marketing websites state that home equity contracts have “no monthly payments” and “no interest,” and are available to homeowners who have no income and low credit scores.

- The industry is small but has expanded in recent years, driven in part by an emerging secondary market for securitizations. The first home equity contract company was founded in 2006 and competitors joined the market starting in 2015. The market got a boost in 2023 when Morningstar DBRS started rating securitizations with home equity contracts. In the first 10 months of 2024, the four largest home equity contract companies securitized approximately $1.1 billion backed by about 11,000 home equity contracts. Despite the expansion, home equity contracts are still a niche product in comparison to the 1.2 million HELOCs originated during the four quarters ending 2024 Q2.

- Homeowners must repay a home equity contract with a single payment—the amount of which can be difficult to predict and can run in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Each home equity contract company has its own methodology for calculating the repayment amount, but all generally require full repayment by the end of the term, typically 10 to 30 years, or upon a trigger event such as the sale of the home. The repayment amount is based, in part, on the home’s value at the time of the settlement, which makes the total financing cost uncertain.

- Home equity contracts are expensive compared to other home-secured financing options. Home equity contracts often carry features that boost the settlement amount due from the consumer and insulate home equity contract providers from losses in all but extreme home price declines. Under many contracts, the settlement amount grows at a rate of 19.5-22% per year in the early years, which is substantially higher than interest rates on most home-secured credit, and somewhat less than interest rates on unsecured debt like credit cards.

- Home equity contracts are complex financial contracts that can be difficult to understand or compare to other options, and companies currently provide non-standardized disclosures. The final repayment amount depends on a complex interplay of numerous factors, some of which won’t be known prior to settlement. For example, some home equity contract companies credit the homeowner for renovations or improvements that increase the value of the home, while others do not. As another example, some home equity contract companies place an upper limit on the total settlement amount a consumer could owe them, while others have no limit to the amount a consumer might end up paying.

- Consumer complaints are limited so far but provide a preview of consumers’ issues with home equity contracts. A review of complaints shows homeowners that felt frustrated or even misled about various aspects of home equity contracts—including confusion about the financing terms, surprise at the size of the repayment amounts, disputes about appraisal values, difficulty with refinancing due to the existence of the home equity contract, and frustration that they felt their only option to get out of the contract was to sell their home.

- Consumers could be forced to sell their homes to pay off the contracts. These contracts generally require that consumers repay the full settlement amount by the end of the term or upon a triggering event. Those who want to stay in their homes must either liquidate other assets or qualify for enough financing to repay the home equity contract in full. Homeowners who cannot pay the full settlement amount at the end of term risk having to sell their home or face foreclosure.

According to the CFPB, home equity contracts carry features that echo some of the risky loan structures that were common in the lead up to the 2008 housing crisis. Home equity contracts advertise “zero monthly payments,” require consumers to assume all costs for property taxes, hazard insurance and property maintenance, and require a large settlement payment, similar to the loans originated in the early 2000s that were negative amortizing and required a balloon payment at the end of the loan term. Home equity contracts also tout loose underwriting requirements, enabling them to reach homeowners with low credit scores or little to no income.

The bureau reported that home equity contract offerings have primarily targeted existing homeowners. However, as of late 2024, at least two companies have announced new home equity contracts aimed at homebuyers. Product details are limited, but these home equity contracts appear to be in second-lien position behind a more traditional mortgage and would replace part of the homebuyer’s down payment.

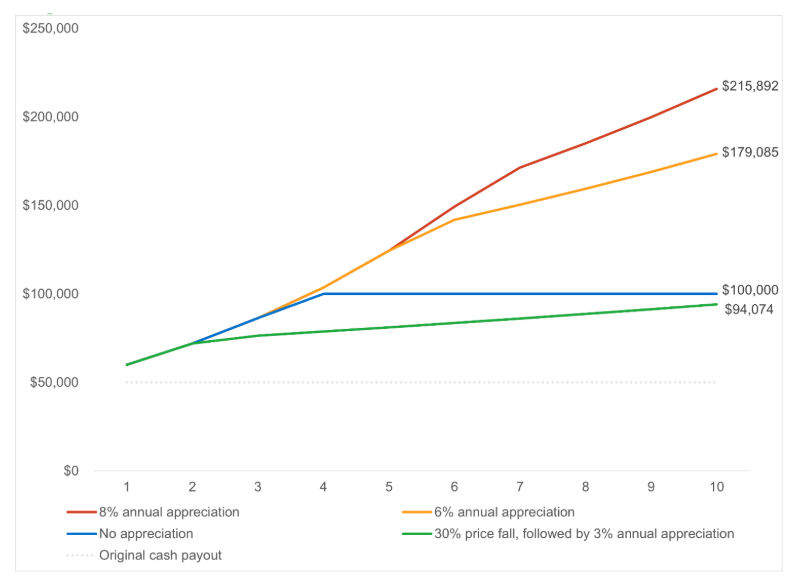

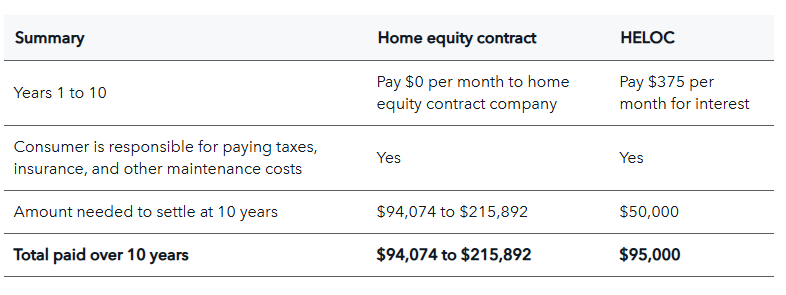

In the report, the CFPB analyzes the cost of these contracts to consumers versus other home-secured finance options.

In the example, a consumer gets a mainstream $50,000 HELOC with a 9% interest rate and interest-only payments for 10 years. Their payments would be $375 per month for the first 10 years. After three years, they would have paid $13,500 in interest. At 10 years, they would have paid $45,000 in interest and still owe the original $50,000. In comparison, using the example home equity contract the CFPB detailed in the report with a $50,000 upfront payment, the consumer would have to pay between $94,074 to $215,892 under the home price appreciation scenarios discussed in the report. The home equity contract would be more expensive overall than the HELOC if the home appreciates. It would be less expensive overall only if the home value falls by at least 5% from its starting value 10 years earlier. However, under the strongest home price appreciation scenarios, the consumer would repay more than twice as much overall for the home equity contract than for the HELOC.

Contact ALTA at 202-296-3671 or [email protected].